“A thrilling tale of World War II!”

“A spine-tingling adventure to the bottom of the sea!”

“A death-defying trip to outer space!”

All taglines that might catch my attention, yes, especially when I was a kid gobbling up everything I could get my greedy little eyes on.

Almost certainly not coincidentally, these were also the kinds of stories I wanted to write in later years. Yes, I loved classic literature with the symbolism of Moby-Dick, the understated elegance of Hemingway, and the keen social insight of George Orwell.

But I also longed for adventure.

One of the favorite authors in my teen years was thriller writer Alistair MacLean. He wrote using settings like WWII in Where Eagles Dare, a high-wire circus in, well, Circus, and the Arctic in Ice Station Zebra. These places and times fascinated me, and I itched to write my own adventures.

And so I tried to do just that.

When Plot Overshadows Character

For some reason, however, I just could not make the yarns spin out just right. I would either reach the end far too soon, leaving the entire thing feeling flat, or it would simply hit a wall and subsequently die in a dusty drawer or, later, hard drive (also dusty).

This malady went on for years. “Well, maybe I just don’t have it,” I mused, not quite defining what “it” actually was; it just felt comforting to have some sort of excuse for failing.

I would leave off writing for a while and pursue some other interest. But all it took was an encounter with some exciting story, and I would feel the urge to start anew.

Slowly — very slowly, as I admit to not having fully learned this lesson yet — I began to realize what was going wrong.

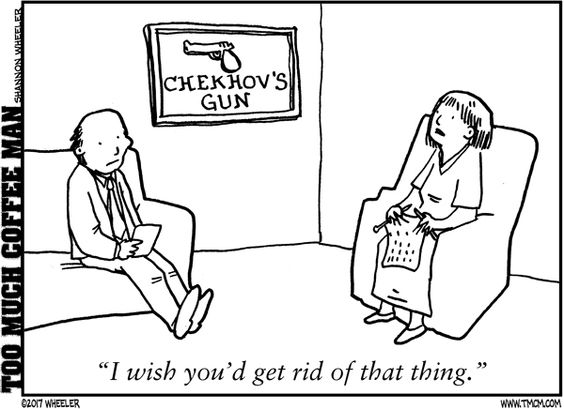

I was making the story about what it was that had excited me in the first place: the raging battle, the far-flung land, the ancient time.

But those times and places were not what the stories I read were about. They were about the people. And I was neglecting them, in some cases badly so.

The characters in those successful stories were living and breathing, real people with desires, obstacles, relationships, fears, contradictions, and private jokes only they understood. My characters were nothing more than tour guides wearing plot armor, cheerfully pointing at explosions — excuses to write something exciting.

What Makes Adventure Stories Work

Now, there is obviously nothing wrong with those breathtaking settings. I still love them. And it may be what attracts a reader in the first place. But they keep reading for the people, the characters — those hapless creatures struggling through whatever exciting scene has been splashed across the cover.

What makes a World War II story work isn’t the whistling bombs over London or the booming thud of the AA guns. It’s the mother huddled in the dimly lit subway with her child wrapped in her arms as she sings a lullaby and wonders if her husband is still alive somewhere on the battlefield.

What makes a sweeping historical of ancient Rome work isn’t the roaring coliseum and clash of blades. It’s the desperate slave inside the gladiator helmet who knows that freedom is only one more victory away. And who’s starting to wonder if freedom is worth it if everyone he loves will be dead by then.

It’s about the people — the characters — and it always is.

Certainly, character-driven literary efforts live or die by them. But what I didn’t understand (and still often don’t) is that even the most plot-driven thrillers need characters the reader cares about. Because if the reader doesn’t care about the people, they’re not going to care what happens to them.

I thought I was writing adventure stories. Nope, not really. Turns out I was just writing postcards from exciting places and times.

The real adventure is always waiting in the people facing those exciting places and times.